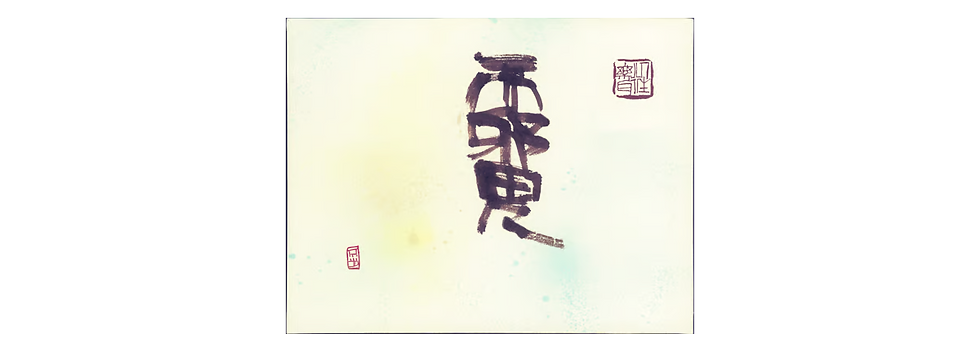

Prince Shōtoku and Japanese Calligraphy – Writing as the Foundation of Thought and Nationhood

- 清水 芳樹

- 2025年5月24日

- 読了時間: 3分

When discussing Japanese Calligraphy, it’s easy to jump straight to the iconic figures of the Heian period. Yet the true roots of this art form stretch further back—to the visionary mind of Prince Shōtoku (Umayado no Ōji), a statesman and spiritual leader of the Asuka period (6th–7th century).

Why is he so significant to the history of Japanese calligraphy? Because he was the first to establish writing not simply as a practical skill, but as a profound tool for conveying philosophy, governance, and spiritual belief. In many ways, he laid the ideological and artistic foundations upon which the Japanese calligraphic tradition would later flourish.

A Statesman, Philosopher, and Cultural Architect

Prince Shōtoku is widely known for composing the Seventeen-Article Constitution, promoting Buddhism, and dispatching envoys to China. But beyond politics and diplomacy, he envisioned a civilized Japanese nation rooted in spiritual wisdom and cultural depth.

At the heart of his vision was the written word. The adoption of kanji, imported from China, was not only necessary for understanding Buddhist texts, but also essential for articulating Japan’s own emerging national identity. For Shōtoku, writing was a sacred act—a means of encoding and transmitting both divine truth and state ideology.

The Hokke Gisho – A Testament in Ink

One of the most important calligraphic legacies attributed to Prince Shōtoku is the Hokke Gisho, a commentary on the Lotus Sutra. Believed to be written by the prince himself, it is considered Japan’s oldest surviving manuscript.

Rendered in kaisho (standard script) influenced by the refined styles of China’s Six Dynasties period, the Hokke Gisho exemplifies not only elegant form but also deep spiritual intent. Each brushstroke reflects devotion to Buddhism, clarity of thought, and a desire to educate and guide the nation.

Diplomacy That Elevated Calligraphy

Shōtoku’s dispatch of envoys—most notably Ono no Imoko—to China opened the door to advanced writing techniques and bureaucratic documentation practices. Through these missions, Japan gained direct exposure to Chinese calligraphic philosophy, which would influence both governmental administration and cultural aesthetics for centuries to come.

Under his guidance, calligraphy evolved from a religious necessity to a national discipline. The idea that official documents should not only communicate but be written with visual harmony and elegance took root during this period.

Writing as a Spiritual Practice

What truly set Shōtoku apart was his belief that writing was more than inscription—it was a spiritual and symbolic act. Characters carried meaning beyond the literal. They embodied belief, reverence, and philosophical clarity.

Inspired by this belief, temples and state officials began to view writing with awe and respect. Sutra copying became both a meditative and ritual act, and political documents were approached with the same reverence as religious ones. This idea—that one’s writing reflects one’s character and soul—would later become a core principle of Japanese Calligraphy: Sho wa hito nari (書は人なり) – “Calligraphy is the person.”

Conclusion: The Spirit Behind the Stroke

The Japanese calligraphy we admire today owes much to the ideological and cultural foundations established by Prince Shōtoku. He recognized that writing was a mirror of the mind, and that the brush could convey far more than words—it could shape nations, express belief, and preserve identity.

Through his legacy, we are reminded that calligraphy is not merely an artistic pursuit, but a spiritual journey and cultural statement. Every character we write is part of a lineage that began not with artists alone, but with a philosopher-prince who saw in ink the future of his country.

Coming up in Column #11: “The Rise of Kana – How Japan Created Its Own Script and Transformed Calligraphy Forever.”

If you’d like this formatted for a luxury blog, a cultural newsletter, or social media engagement, I’m happy to provide those as well!

Experience authentic Japanese calligraphy:

コメント