The History of Japanese Calligraphy – From Ancient Influence to National Art

- 清水 芳樹

- 2025年5月24日

- 読了時間: 2分

Introduction: A Cultural Legacy Written in Ink

The history of Japanese Calligraphy (Shodo) is a journey through centuries of cultural, political, and artistic evolution. What began as an imported writing system eventually transformed into a uniquely Japanese art form—both spiritual and aesthetic in nature. Understanding the history of Shodo is essential to appreciating its deep roots in Japanese identity.

The Chinese Origins: Introduction of Kanji (5th–6th Century)

Japanese Calligraphy owes its origins to Chinese calligraphy, introduced to Japan through envoys, monks, and scholars during the 5th and 6th centuries. Along with Buddhism, kanji (Chinese characters) were brought to Japan and became the foundation for official communication, religious texts, and early literary works. At this stage, calligraphy closely followed Chinese techniques and styles.

The Nara Period (710–794): Calligraphy as Sacred Practice

During the Nara Period, calligraphy became deeply associated with Buddhism. Sutras were copied by hand in exquisite detail as a form of devotion and meditation. The act of writing was considered a spiritual offering. Many examples from this era, such as the Hyakumantō Darani, remain national treasures today.

The Heian Period (794–1185): The Birth of Japanese Style

The Heian Period marks the true beginning of Japanese-style calligraphy. As kana (hiragana and katakana) emerged, calligraphers developed a writing style that was more fluid and expressive. This era saw the rise of elegant, flowing scripts in court poetry, personal letters, and literature—most notably in works like The Tale of Genji. Calligraphy became a refined practice among aristocrats and nobles.

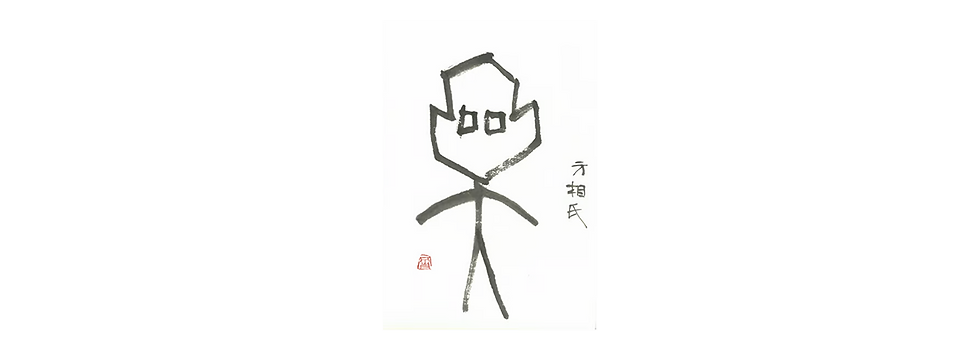

The Kamakura and Muromachi Periods (1185–1573): Zen and Simplicity

The influence of Zen Buddhism during these periods brought a more spiritual and minimalist approach to calligraphy. The ink painting and calligraphy of Zen monks, often done in bold, freehand strokes, emphasized inner clarity over visual perfection. This aesthetic of wabi-sabi—beauty in imperfection—became a defining trait of Japanese Calligraphy.

The Edo Period (1603–1868): Popularization and Education

During the peaceful Edo era, calligraphy became more widespread across social classes. It was taught in schools (terakoya) and used in business, poetry, and art. Calligraphy manuals were printed and distributed, making the practice more accessible. It was no longer just for monks and nobles, but for everyday people.

Modern Era to Present: Tradition Meets Innovation

In modern Japan, Shodo continues to thrive as both a traditional art and a contemporary practice. While it remains part of school education, it is also embraced by professional artists and designers. Calligraphy is exhibited in galleries, adapted into digital media, and practiced as a form of personal mindfulness.

Conclusion: A Timeless Art

The history of Japanese Calligraphy is a story of transformation—absorbing outside influences and shaping them into something distinctly Japanese. It reflects not only the written word but also the evolution of the Japanese spirit. As we continue this series, we’ll explore how these historical roots influence modern calligraphers today.

Coming up in Column #4: “The Spirit of the Brush – Shodo and Zen Buddhism.” Don’t miss it.

コメント